No, I am not contradicting to myself at all. You will see.

I don't, but I'm sure you'll be patient and explain it better.

If a fish went to amphibian in Devonian time, then why not more fishes came up in Triassic, or in Cretaceous or in Eocene time?

Are you sure there weren't any? I wouldn't swear on it, I wouldn't even swear that no such fossils have been found, and I suspect that I know more about animals both extant and extinct than you do.

Besides, just how often does something have to happen NOT to be a problem for evolution in your opinion?

Now it seems we have a recent species came out of water onto the land (I might be wrong on this). If so, where are the others?

They are all over the world. Even eels can wiggle a fair distance over land when they migrate.

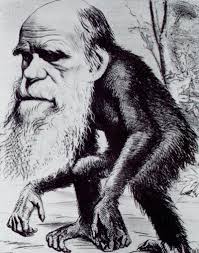

Am I very consistent along this line of thinking? It is a big problem for evolution. The process is incredibly selective and is almost equivalent to creation. In fact, this argument can be applied to all strange animals shown in this thread. Tell me honestly, when you look at these odd balls, what are you thinking about evolution? How did each one of them evolve into existence?

Oh, I love my oddballs. I'll also tell you a secret: those two worms whose portraits I posted are no oddballs at all. There are thousands of similar species swimming, crawling, burrowing everywhere in the world's seas. I take it the winged snails ("sea butterflies" or "pteropods" if you want to look them up) are also a fairly common kind of marine animal. Nothing odd about them at all, except the fact that you don't encounter them as often as, say, sparrows.

(Speaking of sparrows, you'd never guess what oddballs

dunnocks are. By their looks, they are among the least exciting birds here in Britain, but they have incredibly diverse breeding systems. You can see all kinds of arrangements in dunnocks. One male+one female, one male+two females, one female+two males, two females+two males... sometimes, in the same birds in different years. And it's all evolution's fault

)

I know this would be your argument. This is probably the only one you can come up with. But I guess you might also know in your heart that it does not work.

There is rarely any particular niche for any particular one animal. There must be some other animals around and make it a habitat for a community.

How does that mean that there aren't particular niches? Communities define niches, yes (there's no niche for nectar-eaters in coral reefs). But I don't get your argument here.

According to the niche idea, all these animals will share the same character of that particular niche. And we would expect to see a common denominator in the biology of all animals lived in that niche and it reflects the nature of that niche. This consideration pretty much eliminated the possibility of any real "unique" feature in any single animal species.

How so? Each species that adapts to a particular niche brings its entire (unique) evolutionary history into it. Swallows and dragonflies are both fast fliers with excellent vision that catch insects in the air. But they achieve this in completely different ways, because they had very different starting points.

Incidentally, you do see some amazing examples of parallel evolution where the starting points

were very similar. Three- and nine-spine sticklebacks repeatedly invaded freshwater lakes, and when they did, they lost their pelvic spines and much of their armour. (The two reasons I recall are less calcium available in freshwater than in the sea, and different predators. Dragonfly larvae apparently love to grab little fish by their spines...) They not only evolved similar morphologies, they also did it using the

same genetic mechanism at least twice.

The same sort of body and jaw shapes appeared independently in cichlid fish adapted to similar niches in different lakes (

pretty picture, read the caption!).

Horses and litopterns were separated by oceans for tens of millions of years, but some of the latter developed eerily horse-like limbs*. (

the foot of Diadiaphorus, a horse-like litoptern, and

that of Merychippus, an extinct horse.

Thoatherium, another of the "fake horse" litopterns, went all the way to one-toed, but pictures of the foot don't seem to exist on the internet

)

*Or shall we say, some horses developed eerily litoptern-like limbs, as the feet of

Thoatherium were "horse-like" when real horses were still running about on three toes...

)

)