-

Starting today August 7th, 2024, in order to post in the Married Couples, Courting Couples, or Singles forums, you will not be allowed to post if you have your Marital status designated as private. Announcements will be made in the respective forums as well but please note that if yours is currently listed as Private, you will need to submit a ticket in the Support Area to have yours changed.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Evolution Lesson

- Thread starter PsychoSarah

- Start date

Well, no, perhaps there wasn't a huge amount of intermingling, but there was some.

There was as much intermingling as we would expect from separate species who occasionally produce a hybrid.

There is also growing evidence that human/Neanderthal hybrids may have suffered from infertility. It is still way to early to call this conclusive, but it is an interesting bit of information.

"Some of the genes, meanwhile, appear to have led to fertility problems. For instance, Sankararaman found that the X chromosome is almost devoid of Neanderthal DNA. This suggests that most Neanderthal DNA that wound up on the X chromosome made the bearer less fertile – a common occurrence when related but distinct species interbreed – and so it quickly disappeared from the human gene pool. “Neanderthal alleles were swept away,” says Sankararaman."

Neanderthal-human sex bred light skins and infertility

Upvote

0

tansy

Senior Member

There was as much intermingling as we would expect from separate species who occasionally produce a hybrid.

There is also growing evidence that human/Neanderthal hybrids may have suffered from infertility. It is still way to early to call this conclusive, but it is an interesting bit of information.

"Some of the genes, meanwhile, appear to have led to fertility problems. For instance, Sankararaman found that the X chromosome is almost devoid of Neanderthal DNA. This suggests that most Neanderthal DNA that wound up on the X chromosome made the bearer less fertile – a common occurrence when related but distinct species interbreed – and so it quickly disappeared from the human gene pool. “Neanderthal alleles were swept away,” says Sankararaman."

Neanderthal-human sex bred light skins and infertility

Thanks

Upvote

0

Ophiolite

Recalcitrant Procrastinating Ape

In northern climes they are more likely to suffer the effects of vitamin D deficiency. This could lead to soft bones and improper skeletal development. This has two implications: firstly they may be more prone to accidental death before having an opportunity to reproduce; secondly, the impact on their physical and mental wellbeing may render then less attractive as a mate.But why would darker skinned people be at a disadvantage when it comes to reproduction?

I have no idea, but the option is available, which was not the case when the ancestors of the Swedes, for example, were losing much of their melanin and developing long noses to warm the cold air before it hit their lungs.Also, do present-day Africans living in the west (countries such as Britain or ones where there is a lot less sun) take vitamin supplements generally speaking?

Correct, but I am not sure in what way it is relevant.Obviously when a black person marries a white person, then their children tend to have paler skin. However, I have read that occasionally someone has given birth to a black person totally unexpectedly, as there was some (perhaps unbeknownst to them) black ancestry in their family.

Upvote

0

tansy

Senior Member

In northern climes they are more likely to suffer the effects of vitamin D deficiency. This could lead to soft bones and improper skeletal development. This has two implications: firstly they may be more prone to accidental death before having an opportunity to reproduce; secondly, the impact on their physical and mental wellbeing may render then less attractive as a mate.

I have no idea, but the option is available, which was not the case when the ancestors of the Swedes, for example, were losing much of their melanin and developing long noses to warm the cold air before it hit their lungs.

Correct, but I am not sure in what way it is relevant.

I'm trying to understand how these things work...it only may be relevant in that if there is gradual change in people according to their environment, eventually certain traits may be completely eliminated? As long as there is a particular gene still lingering about so to speak (is it recessive genes I'm thinking about, rather than dominant?), could that rematerialise even thousands of years after it was more common? Supposing for example, half the people in a particular population had blond hair and half had black hair, but for some reason for decades or centuries or millennia, no-one was born with black hair...would it be possible for someone to suddenly be born with black hair, and everyone would be completely taken by surprise? Could that gene remain dormant, so to speak, for that long?

Sorry, not explaining my question well, but am trying to understand the relationship between what is inherently present in genetic material and what might actually gradually change (mutate?) or be lost, but without other human contact from another population, so that certain traits would become more or less 'fixed'..the new 'normal' if you like.

Upvote

0

Ophiolite

Recalcitrant Procrastinating Ape

My understanding is it is as you have described. Think of it this way. Genes that are useful tend to be spread through a population and become normal, or at least common. Genes that are disadvantageous tend to be eliminated from the population.

But in both cases these are tendencies. Disadvantageous genes may "hang around" for a considerable time if they are carried by individuals who have lots of really advantageous genes. And vice versa, when a beneficial mutation first occurs it may be eliminated early on by bad luck.

And, as we see in the case of pigmentation, advantageous genes in one environment may be a disadvantage in another.

My population genetics statistical skills are sorely lacking so I do not want to comment on how many generations a rare recessive gene might "hang around" before being expressed, but you have the principle down that it will do so for some considerable time.

But in both cases these are tendencies. Disadvantageous genes may "hang around" for a considerable time if they are carried by individuals who have lots of really advantageous genes. And vice versa, when a beneficial mutation first occurs it may be eliminated early on by bad luck.

And, as we see in the case of pigmentation, advantageous genes in one environment may be a disadvantage in another.

My population genetics statistical skills are sorely lacking so I do not want to comment on how many generations a rare recessive gene might "hang around" before being expressed, but you have the principle down that it will do so for some considerable time.

Upvote

0

- Dec 25, 2003

- 42,070

- 16,820

- Country

- United States

- Gender

- Male

- Faith

- Atheist

- Marital Status

- Private

I assume that modern day pygmies and a masai could have children? Or maybe not?

Masai aren't particularly tall. You're probably thinking of Dinka.

Upvote

0

Supposing for example, half the people in a particular population had blond hair and half had black hair, but for some reason for decades or centuries or millennia, no-one was born with black hair...would it be possible for someone to suddenly be born with black hair, and everyone would be completely taken by surprise?

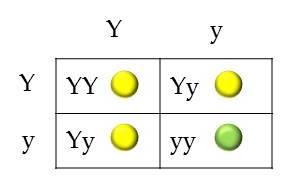

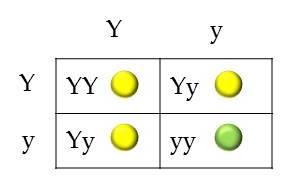

If no one had been born for centuries without blond hair this would indicate that the allele is gone from the population. If the allele is recessive and still present in the population then it is highly probable that two people with the recessive allele would have children with blond hair. If both parents are heterozygous (i.e. have the black and blond allele) then 25% of their children will be homozygous (two of the same allele) for the blond allele, on average. It goes back to the old Punnett squares that we were taught in grade school:

If the capital Y is dominant black hair and the little y is recessive blonde hair, then 3 in 4 children will have black hair and 1 in 4 will have blond hair. Also, 2 out of 4 children will be carriers of the blond allele.

Upvote

0

tansy

Senior Member

If no one had been born for centuries without blond hair this would indicate that the allele is gone from the population. If the allele is recessive and still present in the population then it is highly probable that two people with the recessive allele would have children with blond hair. If both parents are heterozygous (i.e. have the black and blond allele) then 25% of their children will be homozygous (two of the same allele) for the blond allele, on average. It goes back to the old Punnett squares that we were taught in grade school:

If the capital Y is dominant black hair and the little y is recessive blonde hair, then 3 in 4 children will have black hair and 1 in 4 will have blond hair. Also, 2 out of 4 children will be carriers of the blond allele.

Thanks, that's interesting (Afraid I don't know anything about Punnett squares,never came across them either in primary or secondary school..not called that anyway LOL..perhaps they call them something else in the UK). I also only did any kind of science until age just about 14 and was never really taught anything about evolution, genetics or anything, hence my very unknowledgeable questions.

I know I could get a book out of the library or research some of this stuff on the web. However, then one ends up either reading TOO simplistic stuff (like for 5 year olds or something) or it gets too complicated and one ends up having to find out what every other technical word means. Having a back and forth question and answer thing like this helps me wrap my head around stuff a bit better. Thanks

Upvote

0

Thanks, that's interesting (Afraid I don't know anything about Punnett squares,never came across them either in primary or secondary school..not called that anyway LOL..perhaps they call them something else in the UK). I also only did any kind of science until age just about 14 and was never really taught anything about evolution, genetics or anything, hence my very unknowledgeable questions.

I know I could get a book out of the library or research some of this stuff on the web. However, then one ends up either reading TOO simplistic stuff (like for 5 year olds or something) or it gets too complicated and one ends up having to find out what every other technical word means. Having a back and forth question and answer thing like this helps me wrap my head around stuff a bit better. Thanks

You're welcome.

Please continue to ask any questions that you may have and we will try to answer them to the best of our ability.

Upvote

0

Well, both yes and no. Random mutation could always have a chance of reintroducing a trait (hence why certain deadly conditions that are carried by dominant genes and kill before reproductive age can persist), though it will be unlikely to ever become as prevalent as it once was through natural selection if all the people that expressed the trait suddenly died.I'm trying to understand how these things work...it only may be relevant in that if there is gradual change in people according to their environment, eventually certain traits may be completely eliminated?

Whenever a population is brought near extinction, genetic variety suffers, and certain genes are lost to the population. However, in natural selection, there is no intent, so the genes lost could be benign or harmful or neutral, just by chance of what parts of the population die. Over time, populations can and do recover from these genetic bottlenecks if they survive long enough, and genetic variation will increase back to what it used to be. This, however, takes many, many generations. Cheetahs went through an extreme genetic bottleneck about 10,000 years ago, such that all modern cheetahs are descended from fewer than a dozen survivors. To this day, all cheetahs are compatible organ donors with each other, because they lack genetic diversity to such an extent.

Technically, yes, and you are thinking of recessive genes. It would be unusual for a freely breeding population to need that much time, even with the long human generations, but it could happen, hypothetically.As long as there is a particular gene still lingering about so to speak (is it recessive genes I'm thinking about, rather than dominant?), could that rematerialise even thousands of years after it was more common?

Well, black hair is the dominant gene of the two, but if you applied this situation as the people with blond hair dying out, it would still be possible for a blond haired child to be born, even after generations of it not happening. It'd just be unlikely to take that long, unless the majority of black haired carriers of the blond hair genes also died. Furthermore, thanks to random mutation, it would be possible for a blond haired person to be born even if all people with the genes for that hair color died out some time before, it certainly wouldn't be guaranteed, though.Supposing for example, half the people in a particular population had blond hair and half had black hair, but for some reason for decades or centuries or millennia, no-one was born with black hair...would it be possible for someone to suddenly be born with black hair, and everyone would be completely taken by surprise? Could that gene remain dormant, so to speak, for that long?

The only genes that almost never change are the hox genes, which control how developing embryos grow and develop their bodies in the womb or egg. This is because most changes to these genes would result in nonviable embryos that would die. Thanks to that, they are very much retained and similar even between species that aren't closely related, such as humans and sharks.Sorry, not explaining my question well, but am trying to understand the relationship between what is inherently present in genetic material and what might actually gradually change (mutate?) or be lost, but without other human contact from another population, so that certain traits would become more or less 'fixed'..the new 'normal' if you like.

However, no gene is immutable, for even a mutation in a hox gene can be neutral or benign, it's just relatively uncommon. How likely a gene is to experience a mutation has much more to do with it's position on the DNA strand than it's role, with genes located more towards the center being more protected and mutating less than those more towards the ends. No trait is fixed. Nothing is inherent either, not even the nucleotide bases of DNA itself, as there are a number of conditions associated with one of the usual 4 bases being replaced by a nucleotide not usually associated with DNA, such as uracil, which is a typical component of RNA.

Furthermore, so many codons (units of base pairs that code for an amino acid) are redundant and do the same thing that I could artificially cause mutations in more than a tenth of the genes of a developing human embryo and still have said embryo grow up to appear as a normal human, and even be capable of reproduction. Most mutations do pretty much nothing, because most occur on parts of DNA that aren't even genes or are redundant changes to genes.

Upvote

0

tansy

Senior Member

Well, both yes and no. Random mutation could always have a chance of reintroducing a trait (hence why certain deadly conditions that are carried by dominant genes and kill before reproductive age can persist), though it will be unlikely to ever become as prevalent as it once was through natural selection if all the people that expressed the trait suddenly died.

Whenever a population is brought near extinction, genetic variety suffers, and certain genes are lost to the population. However, in natural selection, there is no intent, so the genes lost could be benign or harmful or neutral, just by chance of what parts of the population die. Over time, populations can and do recover from these genetic bottlenecks if they survive long enough, and genetic variation will increase back to what it used to be. This, however, takes many, many generations. Cheetahs went through an extreme genetic bottleneck about 10,000 years ago, such that all modern cheetahs are descended from fewer than a dozen survivors. To this day, all cheetahs are compatible organ donors with each other, because they lack genetic diversity to such an extent.

Technically, yes, and you are thinking of recessive genes. It would be unusual for a freely breeding population to need that much time, even with the long human generations, but it could happen, hypothetically.

Well, black hair is the dominant gene of the two, but if you applied this situation as the people with blond hair dying out, it would still be possible for a blond haired child to be born, even after generations of it not happening. It'd just be unlikely to take that long, unless the majority of black haired carriers of the blond hair genes also died. Furthermore, thanks to random mutation, it would be possible for a blond haired person to be born even if all people with the genes for that hair color died out some time before, it certainly wouldn't be guaranteed, though.

The only genes that almost never change are the hox genes, which control how developing embryos grow and develop their bodies in the womb or egg. This is because most changes to these genes would result in nonviable embryos that would die. Thanks to that, they are very much retained and similar even between species that aren't closely related, such as humans and sharks.

However, no gene is immutable, for even a mutation in a hox gene can be neutral or benign, it's just relatively uncommon. How likely a gene is to experience a mutation has much more to do with it's position on the DNA strand than it's role, with genes located more towards the center being more protected and mutating less than those more towards the ends. No trait is fixed. Nothing is inherent either, not even the nucleotide bases of DNA itself, as there are a number of conditions associated with one of the usual 4 bases being replaced by a nucleotide not usually associated with DNA, such as uracil, which is a typical component of RNA.

Furthermore, so many codons (units of base pairs that code for an amino acid) are redundant and do the same thing that I could artificially cause mutations in more than a tenth of the genes of a developing human embryo and still have said embryo grow up to appear as a normal human, and even be capable of reproduction. Most mutations do pretty much nothing, because most occur on parts of DNA that aren't even genes or are redundant changes to genes.

Thanks very much for that info

Sort of related to all that, how does one decide what is 'abnormal' and maybe not desirable, that is, something has gone wrong at some stage of development. That sounds disrespectful, but I don't mean it that way. What I mean by that is that some people are born with disabilities for various reasons, which aren't very advantageous, like perhaps being born with no legs. But in some countries in particular (can't remember where) there are people who grow long and thick hair all over their bodies, I can't remember what the condition is called. But apart from the fact that, short of shaving the hair off continually, they can find it hard to get work (people would get rather freaked out, perhaps), I can't see any particular disadvantage. Not putting this well, not sure of the right terminology...what I'm trying to say is, supposing this were to happen with more and more people, couldn't it just be seen as adaptation or evolution, not a 'condition' or 'syndrome' or whatever it is? Just the same as some people have blue eyes, some brown or whatever.

Oh, and I've just remembered, you know these cases of children ending up living all by themselves in jungles and things? I saw a documentary a long while back where a small child had ended up living in the forest or jungle (perhaps in India?). The monkeys I think helped look after him. Anyhow, what was interesting was, that he had actually grown longer hair all over his body. I wondered why that would happen. Would it happen to anyone living long enough in those conditions? That doesn't appear to happen to small tribes that live in fores/jungle situations.

Last edited:

Upvote

0

Thanks very much for that info

Sort of related to all that, how does one decide what is 'abnormal' and maybe not desirable, that is, something has gone wrong at some stage of development.

The ultimate arbiter of what is and isn't desirable is how successful your descendants are at making more descendants. It all comes down to good ol' natural selection. What helps your grandchildren and descendants be successful is what gets passed on.

However, the opposite is not necessarily true. Just because something is passed on does not mean that it is inherently desirable from a fitness standpoint. This is actually part of a very entertaining and interesting metadebate in biology right now called the Adaptionist Bias. Some biologists have fallen into the trap of assuming all physical features in any organism must increase fitness because they have been passed on. The problem is that neutral changes can also be passed on, meaning that just because a feature is kept does not necessarily mean it is helpful.

Oh, and I've just remembered, you know these cases of children ending up living all by themselves in jungles and things? I saw a documentary a long while back where a small child had ended up living in the forest or jungle (perhaps in India?). The monkeys I think helped look after him. Anyhow, what was interesting was, that he had actually grown longer hair all over his body. I wondered why that would happen. Would it happen to anyone living long enough in those conditions? That doesn't appear to happen to small tribes that live in fores/jungle situations.

I'm not aware of that example, sorry to say.

Upvote

0

tansy

Senior Member

The ultimate arbiter of what is and isn't desirable is how successful your descendants are at making more descendants. It all comes down to good ol' natural selection. What helps your grandchildren and descendants be successful is what gets passed on.

However, the opposite is not necessarily true. Just because something is passed on does not mean that it is inherently desirable from a fitness standpoint. This is actually part of a very entertaining and interesting metadebate in biology right now called the Adaptionist Bias. Some biologists have fallen into the trap of assuming all physical features in any organism must increase fitness because they have been passed on. The problem is that neutral changes can also be passed on, meaning that just because a feature is kept does not necessarily mean it is helpful.

I'm not aware of that example, sorry to say.

Hm, yes. But of course, nowadays with modern technology, medicines, blood transfusions, transplants etc, people can still be successful at reproducing and perhaps passing on certain undesirable things, perhaps through many generations. And those with certain genetic disabilities or flaws, for want of a better word, can survive a lot longer and lead far more fulfilling and quality lives than they could maybe even a century ago. So perhaps human intervention can play a part. (But then, that wouldn't be natural selection or adaptation of course, rather that humans have the capability of overcoming or curing many things).

Of course, that is actually also a scary thing, what scientists are now starting to be able to do with genetic engineering. How far should it be taken? Just as well they weren't quite so advanced a few decades ago...Hitler (or his henchmen) would have had a field day getting his scientists to create the perfect Aryan race with blue eyes and blond hair, and eliminating in one way or another anyone else he thought substandard or subhuman.

I used to read a lot of science fiction when I was a teenager and was quite horrified at some of the stories, little knowing that actually a lot of those things would actually be possible, or nearly - IV fertilisation, cloning etc (of course in the stories these things were being carried out unscrupulously and to get power over people) I found 'The Clockwork Orange' fascinating, and it raised a lot of ethical points...but I digress somewhat.

I tried to find that instance of the feral child on the web, but couldn't find the specific one I was looking for...but no matter. Can't even remember what channel the documentary was on.

Upvote

0

Yup, we are playing some part in preserving people and allowing them to have kids when, without our intervention, they would die long before that point. Were we to actively, say, encourage these people to have more kids, that could be considered artificial selection, but since we are just changing the environment to allow it, we're just lessening the natural selection pressures on our species as a whole.Hm, yes. But of course, nowadays with modern technology, medicines, blood transfusions, transplants etc, people can still be successful at reproducing and perhaps passing on certain undesirable things, perhaps through many generations. And those with certain genetic disabilities or flaws, for want of a better word, can survive a lot longer and lead far more fulfilling and quality lives than they could maybe even a century ago. So perhaps human intervention can play a part. (But then, that wouldn't be natural selection or adaptation of course, rather that humans have the capability of overcoming or curing many things).

A valid question with no concise answer, unfortunately. Is it moral to change the genetics of a developing infant to prevent them from inheriting, say, Huntington's disease? Is it immoral not to do it? Will this impact the preservation of our species in the case of pandemics? There's no universally accepted answer to those questions, and it is unlikely that there will ever be one.Of course, that is actually also a scary thing, what scientists are now starting to be able to do with genetic engineering. How far should it be taken?

You might think that, from a practical standpoint, it should be obvious that we should actively prevent these diseases as much as we can, but it isn't that simple. Doing so reduces genetic diversity; something we depend on so that we don't all die out from one disease. Certain negative conditions, such as Sickle Cell Anemia, have benefits to the carriers of the gene that don't suffer the symptoms; in this case, an increased resistance to malaria. So, actively removing all genetic diseases from our species has risks.

The idea that any given "race" of humans is universally superior to any other is garbage, especially any European ones, which have some of the lowest genetic diversity. Also, there are laws in place in many countries that prevent discrimination on the basis of genes, so, there are some protections that keep possible future practices in mind.Just as well they weren't quite so advanced a few decades ago...Hitler (or his henchmen) would have had a field day getting his scientists to create the perfect Aryan race with blue eyes and blond hair, and eliminating in one way or another anyone else he thought substandard or subhuman.

Upvote

0

Hm, yes. But of course, nowadays with modern technology, medicines, blood transfusions, transplants etc, people can still be successful at reproducing and perhaps passing on certain undesirable things, perhaps through many generations. And those with certain genetic disabilities or flaws, for want of a better word, can survive a lot longer and lead far more fulfilling and quality lives than they could maybe even a century ago. So perhaps human intervention can play a part. (But then, that wouldn't be natural selection or adaptation of course, rather that humans have the capability of overcoming or curing many things).

The difference between natural and artificial is a metaphysical or philosophical one, so I won't delve too deeply into that one.

What I can say is that mutations can compensate for one another. In our case, mutations conferring intelligence can lessen the impact that other mutations we have. Ultimately, fitness is determined by how well an allele is spread through a population, despite our aesthetic judgments.

Of course, that is actually also a scary thing, what scientists are now starting to be able to do with genetic engineering. How far should it be taken? Just as well they weren't quite so advanced a few decades ago...Hitler (or his henchmen) would have had a field day getting his scientists to create the perfect Aryan race with blue eyes and blond hair, and eliminating in one way or another anyone else he thought substandard or subhuman.

We always need to be careful of the naturalistic fallacy. Just because something is natural does not necessarily mean it is morally good. It is natural for bacteria to infect human beings, but we happen to think it is morally good to treat that infection and get rid of the naturally occurring infection.

On top of that, nowhere in the theory of evolution does it state that we should kill any less fit individuals. No scientific theory tells us what we should do, they can only tell us what the consequences of our actions will be.

I tried to find that instance of the feral child on the web, but couldn't find the specific one I was looking for...but no matter. Can't even remember what channel the documentary was on.

The thing about feral children that always fascinated me was the development of their cognitive function. Children who did not grow up around other human beings and experience using language and social skills at a young age often lacked certain cognitive abilities. They couldn't use language at an older age, or solve complex puzzles. Being human and being part of a human society is actually a requirement for our brain to develop properly. Pretty interesting stuff.

Upvote

0

tansy

Senior Member

Yup, we are playing some part in preserving people and allowing them to have kids when, without our intervention, they would die long before that point. Were we to actively, say, encourage these people to have more kids, that could be considered artificial selection, but since we are just changing the environment to allow it, we're just lessening the natural selection pressures on our species as a whole.

A valid question with no concise answer, unfortunately. Is it moral to change the genetics of a developing infant to prevent them from inheriting, say, Huntington's disease? Is it immoral not to do it? Will this impact the preservation of our species in the case of pandemics? There's no universally accepted answer to those questions, and it is unlikely that there will ever be one.

You might think that, from a practical standpoint, it should be obvious that we should actively prevent these diseases as much as we can, but it isn't that simple. Doing so reduces genetic diversity; something we depend on so that we don't all die out from one disease. Certain negative conditions, such as Sickle Cell Anemia, have benefits to the carriers of the gene that don't suffer the symptoms; in this case, an increased resistance to malaria. So, actively removing all genetic diseases from our species has risks.

Sorry, Haven't been able to figure out how to do the multi-quote thing, so have replied in this font.

That is interesting about the malaria resistance. Of course, I suppose if they could somehow stop mosquitos infecting people, then perhaps it would be OK to eradicate sickle cell anemia...but I can see that it must be a very difficult balancing act to do the right thing. It would seem that whatever humans do to improve things (not just disease prevention, but other things), we unwittingly introduce other problems that need resolving.

The idea that any given "race" of humans is universally superior to any other is garbage, especially any European ones, which have some of the lowest genetic diversity. Also, there are laws in place in many countries that prevent discrimination on the basis of genes, so, there are some protections that keep possible future practices in mind.

Oh yes, I quite agree, I certainly wasn't advocating those ideas!! Heaven forbid! But let's just hope that countries continue to scrutinise scientific advances and make sure laws are passed to prevent any abuses or doing anything that might lead to untold damage.

I put my responses in your message above as I haven't figured out yet how to do the multi-quote. I'm sure it used to be different, I could do it before.

Last edited:

Upvote

0

tansy

Senior Member

The difference between natural and artificial is a metaphysical or philosophical one, so I won't delve too deeply into that one.

What I can say is that mutations can compensate for one another. In our case, mutations conferring intelligence can lessen the impact that other mutations we have. Ultimately, fitness is determined by how well an allele is spread through a population, despite our aesthetic judgments.

We always need to be careful of the naturalistic fallacy. Just because something is natural does not necessarily mean it is morally good. It is natural for bacteria to infect human beings, but we happen to think it is morally good to treat that infection and get rid of the naturally occurring infection.

On top of that, nowhere in the theory of evolution does it state that we should kill any less fit individuals. No scientific theory tells us what we should do, they can only tell us what the consequences of our actions will be.

The thing about feral children that always fascinated me was the development of their cognitive function. Children who did not grow up around other human beings and experience using language and social skills at a young age often lacked certain cognitive abilities. They couldn't use language at an older age, or solve complex puzzles. Being human and being part of a human society is actually a requirement for our brain to develop properly. Pretty interesting stuff.

No, I realise that the theory of evolution doesn't state that, I was really just saying that with modern genetic engineering, it would be rather horrifying if people similar to Hitler and his ilk decided that they wanted to use it to eliminate certain groups of people, or 'improve' them. (I think, though I may be wrong, that they thought Australian aboriginals were further down the evolutionary scale than others).

Regarding the development of children, I saw or read several years ago, about orphaned infants/babies in an orphanage somewhere in Europe. They were lying them in cots which had white sheets put all round the sides and thus had no stimulation, nothing to see except the ceiling and from time to time, whoever came and fed them and changed their nappies. They then discovered that these infants didn't thrive or develop as quickly or well as others who had a more stimulating environment.

I wonder if the same would hold true of some other species..if they were separated from their natural kind, would they not develop properly? Of course, I suppose we've seen that with some wild animals, perhaps rescued having been injured or orphaned, got used to humans, but not learnt hunting skills or how to survive in the wild. Yes, it's very interesting

Upvote

0

Something to consider . . .

HIV attaches to a protein on host cells called CCR5. As it turns out, people with a mutation in CCR5 are resistant to HIV. This mutation was just sitting out in the human population, but when HIV came around it turned out to be useful.

People with two copies of the CCR5 delta32 gene (inherited from both parents) are virtually immune to HIV infection. This occurs in about 1% of Caucasian people.

One copy of CCR5-delta32 seems to give some protection against infection, and makes the disease less severe if infection occurs. This is more common, it is found in up to 20% of Caucasians.

The Evolving Genetics of HIV | Understanding Genetics

If we decide to eliminate genetic diversity in the name of human bigotry and bias, we may actually be eliminating mutations that the human population will need farther down the road. A genetically diverse population is the best bet for meeting the challenges our species will face in the future.

HIV attaches to a protein on host cells called CCR5. As it turns out, people with a mutation in CCR5 are resistant to HIV. This mutation was just sitting out in the human population, but when HIV came around it turned out to be useful.

People with two copies of the CCR5 delta32 gene (inherited from both parents) are virtually immune to HIV infection. This occurs in about 1% of Caucasian people.

One copy of CCR5-delta32 seems to give some protection against infection, and makes the disease less severe if infection occurs. This is more common, it is found in up to 20% of Caucasians.

The Evolving Genetics of HIV | Understanding Genetics

If we decide to eliminate genetic diversity in the name of human bigotry and bias, we may actually be eliminating mutations that the human population will need farther down the road. A genetically diverse population is the best bet for meeting the challenges our species will face in the future.

Upvote

0

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 150

- Replies

- 220

- Views

- 11K

- Replies

- 31

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 1K

- Views

- 34K

- Replies

- 33

- Views

- 1K