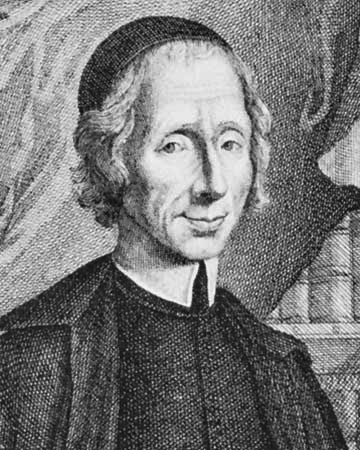

A quote from the early modern philosopher, Nicolas Malebranche "To be a faithful Christian one must believe blindly; but to be a philosopher one must see evidently."

(From

Concerning the Search After Truth)

en.m.wikipedia.org

Do any of y'all have thoughts on these two claims? Is it the case that Christians believe blindly? Must a philosopher "see evidently."

(I take the second claim to be an epistemic one requiring an evidenced foundation, i.e., clear and distinct ideas in the Cartesian fashion. Of course, for Malebranche, this includes God's extra-experiential guarantee)

For me, both claims are too strong, regardless of context. I don't see Christian faith as being without reason, which I take "blind faith" to entail. If blind faith simply means *lack of certainty,* which it likely did for Malebranche, then the claim tells its age, imo.

Malebranch was a convinced believer, and he was also a Cartesian. Like Descartes, he was enamored with the idea of certainty and securing everything down to a certain foundation. If a belief couldn't be secured in some way to certainty, it was not knowledge- strictly speaking. I don't have that kind of epistemic standard. I'm not sure it's possible, and I certainly don't see philosophy as needing a certain foundation in that sense. I'm happy if things are reasonable and not obviously false. We know all kinds of things that can be doubted.

As an aside, Malebranche's occasionalism seems unnecessary and only exacerbates the dualism, but I would agree God guarantees veracity. It just think the divine guarantee is through the created order and not in spite of it or along with it. His occasionalism seems very ad hoc and unhelpful.

I do think both Christian faith and philosophy should proceed in the light of the available evidence, whatever that may be. There has to be some coherence between the availble evidence and my faith. If it is certain, then it must be included. And I think our degree of credulity in the evidence should track its evidentiary value. For instance, if the evidence is strong, I should have a similar credence of belief. But all veritable/credible evidence to which I have access should be a viable aspect of my faith and/or philosophy. Depending on the level of credulity required, I can't simply reject evidence as false because it doesn't seem to fit.

Of course, I see things that way because of my faith, i.e., all truth has one Source. Does that article of faith make it blind, then? I don't think so. First, I have reasons for thinking one Source makes sense. But I also don't think any of us can escape making ontological claims/commitments on the world, i.e. large assumptions about reality, and I don't think we can be certain of the ontological claims we make. No matter how one sees the world, a step of faith is being made somewhere epistemically important. I don't think that's all blind faith. I mean, we all have our reasons. And, I think many people today can live with a lack of certainty. That's where I think many have moved beyond the Cartesian obsession with certainty as an epistemic requirement. Since the time of Malebranche, we have a new physical account that allows for uncertainty. A lot has changed. Certainly for me, I think we can have reasonable faith and a less than certain philosophy.