So why does the Bible give reference to the book of Jasher;

King James Bible

And the sun stood still, and the moon stayed, until the people had avenged themselves upon their enemies.

Is not this written in the book of Jasher? Joshua 10:13

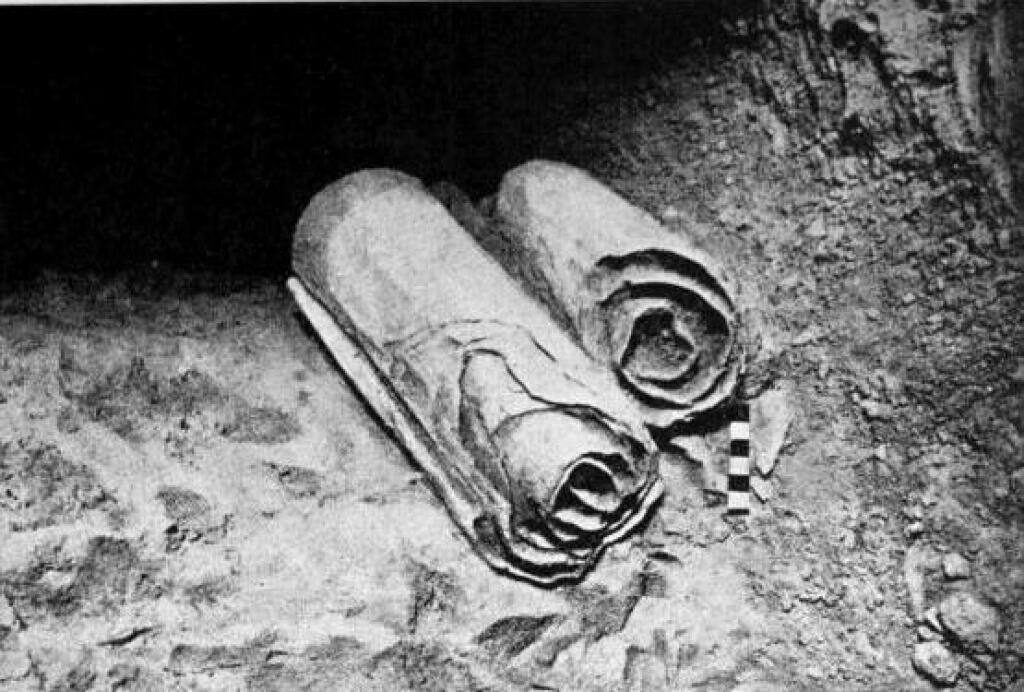

There are several books referenced in the Bible which no longer exist. Jasher is an example of an ancient work which has since been lost. There is also a reference to a now lost work of Iddo the Seer. Like Jasher, this work is no longer extent.

Such texts did exist at one time, and the biblical authors point to them as reference material which was known in their time. However these works, clearly, were not preserved. The ancient communities of faith, first Jewish and later Christian, were concerned with preserving certain texts; not merely for the sake of posterity but rather recognized certain texts as authoritative. This process is known as canonization, from the Greek word kanon, originally referring to a reed used for measurement, the concept of a kanon developed into the idea of a standard, or rule. The Biblical Canon therefore meaning those texts which were to be regarded as standard, and also were authoritative. While this process of canonization was not entirely uniform nor monolithic, we see an emerging consensus about which books are sacred. Where there were debates or disagreements about certain books, it is always a pretty small list of books which are debated. Nobody, for example, would have thought to include Homer's Iliad into the Canon of Sacred Scripture. The overwhelming majority of books that have ever been written were never even conceived as being important enough for inclusion in a list of sacred and authoritative texts. And that includes, for example, the now lost book of Jasher. There is no evidence that, at any time, the Jewish community ever regarded this work as sacred; and its presentation in places like here in Joshua is merely informative and historical.

Enoch is an interesting case for a number of reasons. For one, the text we now call "1 Enoch" isn't a single text; it is an amalgamation of different texts written between ~200 BC and ~100 AD; these were all, originally different books as part of a broad Enochic tradition that existed in 2nd Temple period Judaism. In this period a lot of works were written which focused on usually minor biblical characters, with expansive stories, legends, and often fantastical elements. There are parallels between this and in modern times what we would generally call "fan-fiction". At some point, probably between the 3rd and 5th centuries some of these Enochic texts were brought together and compiled into a single work, which we now call 1 Enoch. And yes, we call it 1 Enoch because there are more Enochic works out there, so there is a 2 Enoch, and a 3 Enoch, and (if memory serves me) even a 4 Enoch. Some of these get truly bizarre; in either 3 or 4 Enoch, written by an unknown Jewish author sometime in the 5th or 6th century the figure of Enoch when he is taken up into heaven is transformed into the powerful angelic being known as Metatron, and bears an almost divine status. In fact later Jewish writers explicitly condemned this work and similar Enochic legends as unacceptable, because it amounted to claiming that there was God and also a kind of Vice-God, a second God, in heaven.

Another reason why 1 Enoch is interesting is because while early Christians were very aware of Enochic texts (one is quoted explicitly in the Epistle of St. Jude in the New Tetament), and some early Christians held them in high esteem (Tertullian of Carthage, around the year 200 AD, seems to regard it as Scripture, but Tertullian is himself an interesting figure because he converted away from orthodox Christianity to the Montanist cult at some point in his life); but the only historic churches which ever ended up taking the Enochic texts seriously enough to include them in a Canon was the Church of Ethiopia, which regards the distinctively Ethiopic version of the late amalgamated Enoch text (e.g. 1 Enoch) in its Canon. Outside of the Ethiopian (and now also Eritrean) Church, 1 Enoch has never received this kind of recognition; but has largely been relegated to interesting historical fiction.

A biblical author quoting, or referring, to another person or text does not in and of itself signify anything beyond a recognition that such a text exists. So, in the Acts of the Apostles, when St. Paul quotes Greek poets and philosophers, this does not mean that these poets and philosophers, nor their works, are to be regarded as Scripture, or sacred. Indeed, the work which Paul quotes that says "We are His offspring" was originally about Zeus, but Paul borrows it, not to speak of Zeus, but instead to apply it to the God of Israel; even as he takes advantage of the altar to the "Unknown God" at the Areopagus in Athens to speak about Israel's God, in order to converse with the Athenian elite and invite them to consider the message of Christ and the Christian Gospel.

Jasher no longer exists, but even if it did, it wouldn't be anything more than a work of purely historical significance. But, and I can't stress this enough: Jasher no longer exists. There are works out there which people claim are the long lost book of Jasher, but these have nothing to do with the work mentioned in the Old Testament. There is, for example, a work of medieval Jewish midrash known as the Sefer ha-Yashar (Book of Jasher), but it's merely medieval Jewish midrash. Worse, however, is that there is an 18th century forgery that still sometimes gets brought up that people claim to be the long lost book of Jasher--but it's not, it is a forgery from only several centuries ago, and even when it first showed up nobody took it seriously, and in fact the person who created the forgery (a British man) was caught and was arrested for it by the British authorities. Because several hundred years ago, just like today, people want to make a quick buck through fraudulent means.

-CryptoLutheran