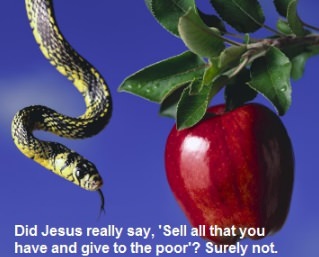

I mean, you're telling the truth. There really are "Contradictions; contradictions everywhere!"

...the only thing is, we Christians are more prone to just call all of those contradictions...

"Sin."

Let's clear up this

contradiction and

sin motif in Biblical literature. Biblical contradictions are seemingly easy to point out. However, there are a wide range of varieties as to why the Biblical texts are contradictory, generally this has to do with P, E, J, D sources in the Biblical texts and much later this has to do with Church Councils in the New Testament, each author is bringing to the table a variation of translation concerning the Bible, historically.

However, there are such issues in the Bible as humans being created in the image of God which tends to violate holy law itself.

Divine image and representation concerning the creation of human life is an exception to the rule of creation by divine fiat, as signaled by the replacement of the simple ... Hebrew command (the jussive) with a personal, strongly expressed resolve, the cohortative. Whereas the earlier jussives expressed God’s will with a third person, nonagentive verb form, the cohortative is both first person and agentive. Unlike the jussives, too, the cohortative doesn’t itself create but prepares or introduces the creative act. With justification, then:

The man and the woman in Gen. I ... are ... created ... by God’s own personal decision (v. 26)—a decision unique in the Priestly document’s whole creation account.

Similarly, God participates more intimately and intensively in this than in the earlier works of creation. As the cohortative form suggests, P’s (P source) God anticipates a more active role, greater control, and stronger personal involvement in the human creation than in his previous seven creative acts. God’s involvement also runs deeper. As P (P source) tells the story, this last creative act coincides with an extraordinary divine event. When God initiates human creation, God takes the opportunity to identify himself, for the first time, in the self-referential first person. At the same time, God’s identity is invested in this human creature and is represented by two characteristics: a divine image and a divine likeness. Humanity resembles divinity through two inherent yet divine features. Of all God’s creations, only humanity is envisioned as comparable to divinity.

V. 27 will corroborate and will execute this vision. Its first clause names the creator, the human creature, and the divine image that God invests in human beings (v. 27aα ). Overlapping with the first, the second clause identifies the divine possessor of the image (v. 27aâ ). The third clause deletes reference to the image yet describes the human creature as a constituent pair (v. 27b). V. 27 therefore will reiterate the unique relationship between God and humanity, explains the relationship, and tracks it from its source to its individual heirs. So, the interpretive details of Gen :26–27 are unclear at best.

To be sure, the characteristics uniquely shared by creator and creature assert “the incomparable nature of human beings and their special relationship to God.”

But when its two nominal components—‘image’and ‘likeness’—are queried, the assertion of incomparability is quickly qualified. For example, what does the ‘image’ of God signify, and how does the human race reflect it? Or, what is a divine ‘likeness’, how does it compare to the divine ‘image’, and how is the ‘likeness’ reflected in humankind? The responses are often unsatisfying. Very little distinction can be made between the two words. The two terms are used interchangeably and indiscriminately and one has to conclude that “image” and “likeness” are, like “prototype” and “original,” essentially equivalent expressions. They do not seek to describe two different sorts of relationship, but only a single one; the second member of the word-pair does not seek to do more than in some sense to define the first more closely and to reinforce it. That is to say, it seeks so to limit and to fix the likeness and accord between God and man that, in all circumstances, the uniqueness of God will be guarded. These statements, then, testify to the problem.

The ‘image’ is problematic in its own right. For in most of its occurrences, íìö ‘image’ is a concrete noun. And as such, it refers to a representation of form, figure, or physical appearance.

Thus if the human race is created in the ‘image of God’, there is an unavoidable logical implication: God must also be material, physical, corporeal, and, to a certain degree, humanoid. Problematic, too, is the intertextual implication of a concrete, human ‘image’. Indeed, the very existence of such an ‘image’ seems to violate the second commandment, which forbids idols and idolatry (Ex 20: – ; Dt : –10; see also Dt :15–19, and, within the Priestly tradition, Lev 19: , 26: ).