When Animal A evolves into Animal B, the process is very slow and over hundreds of thousands of generations. For example, Chimplike (A) into Human (B). Would it be likely that Animal C would have existed as a intermediate creature that evolved from A but ultimately became B at some point during the process of A to B?

Yes. To put it in a slightly different way, if Species A evolved into Species Z, it will evolve though Species B, C, D...W, X, and Y before getting to Species Z. It must do this - it is impossible for an individual of Species A to give birth to an individual of Species Z. Species B through to Species Y

must be there.

Expanding the pile of sand analogy: Let's say a pile of sand (A) will evolve into a pile of grass (B). About 1/2 way into the evolution, the sand grains have green tails (C). Now you have a pile of Sass. It's clearly not a pile of sand nor a pile of grass.

Yep. When something evolves from one thing to another, it will pass through an intermediary stage. Of course, if you saw that intermediary stage, it wouldn't be obviously a transitional. it would be just as valid a species as anything else. Evolution isn't aiming towards some specific goal. If you found Species A through to Species M (with Species M being the present day species), you couldn't predict the qualities of Species Z (which will not be around for a long time). All you can do is say that the lineage that has lead from Species A to Species M will continue, resulting in new species in the future. You might be able to make some educated guesses about the near future, but the further into the future, the less accurate you will be. For example, I can confidently predict that there will still be birds flying in 1 million years. But I can't predict what they will be like. But I sure can't say if there will be birds in 500 million years. And even if they are, I couldn't tell you what they'll be like.

The paradox of the pile did contribute clarity to the slow transformation of creature A to creature B, but because it was only a reduction in populate exercise, it didn't help with the issue that when you finally reach the final grain of sand, it's no longer sand.

Ah, but the analogy wasn't about changing from sand into a non-sand thing. It was about changing from a pile into a non-pile.

In the chimp-like to human evolution...

I'm going to stop you there. Humans didn't evolve from chimps. Both Humans and chimps evolved from a common ancestor. There was a species, say Species 1A, and it was split into two populations. One group became Species 2 and the other group became Species B. Species 2 could be Humans and Species B would be chimps. Species 1A was the common ancestor of chimps AND humans.

we should expect to find a creature (C) that exhibits characteristics of both creatures (A&B). Unless all the morphological differences change at the same rate, it seems we should find a creature that features a subset of fully human characteristics and a subset of fully chimp-like characteristics. In other words, unless the brow, ears, mouth, jaw, hands, hips, hair, eyes, feet, skull, brain, diet, etc all evolved simultaneously at the same rate, we should find a creature (C) that is fully human in at least one aspect, fully chimplike in another, and remaining differences would exhibit something between the start point and end point.

Not quite. To a degree, yes, but it's a mistake to think that fully human features just popped up where they were never there before. Let's say the common ancestor had Trait A, and Humans have Trait B. We wouldn't find that Trait B began popping up. We'd find that Trait A gradually, over many generations, became more and more like trait B.

Maybe all those characteristics did evolve simultaneously and at the same rate? If so, we'd never see a creature with at least one fully human feature and at least one fully chimp feature, but should still see one that is more-or-less exactly between the two. As I partake in this brain exercise, it seems that if all the changes were taking place simultaneously, it is as if the creature knew what it was to become when it started and that can't be correct.

No. Evolution doesn't aim towards a set goal. If you could travel through time and watch the change from chimp/human ancestor to Human, you'll see that the population had traits that were quite ancestor like but these traits slowly became more and more human like.

it's like when they morph people's faces from one to the other. Let';s say you morph from Tom Hanks' face into Anne Hathaway's face. You could look at a particular feature, let's say the eyes. They would start out as Tom's eyes, but as the face slowly morphed, the eyes would become less and less Tom-like and more and more Anne-like.

Continuing my though process: There was a time when the chimp foot changed into a human foot. Did the slight stepwise progression through thousands of generations 'trigger' the change in leg, knee, hip, muscular, and vascular structures? Not to say that a foot mutation started the process, but some beneficial mutation occurred that must have caused the change in supporting components. Those changes in supporting components could have only been considered a beneficial mutation only after the first beneficial mutation. In other words, only after a beneficial mutation occurred in one facet could the change of supporting facets be considered beneficial rather than destructive. What good would an upright posture be if the foot wasn't able to accommodate?

The posture became slowly more and more upright as the foot became more and more human like.

if we take it one step at a time, it could be something like...

The foot becomes a tiny bit more human like, on average, throughout the population. This slightly more human foot might give little benefit by itself, but any individual which could stand slightly more upright would see a slightly larger benefit. The benifit might be tiny, but as long as it was there, it would be enough to give any individual that had it an evolutionary advantage.

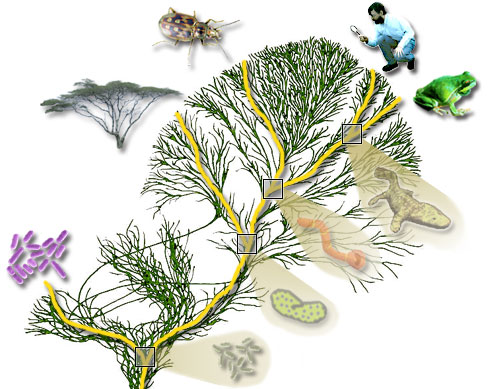

ETA: I hope this post is not misinterpreted as a Crockoduck declaration. I'm interested in exploring the reason why there are no definitively labeled nodes on a tree of life depiction (my original question). The reason given is because "there is no way to ever know." That answer goes against my current logical rendition of "how it all went down". I'm trying to gain clarity by fleshing out what seemingly had to have happened if a creature A is to become creature B over thousands or millions of generations.

You'd be very interested in ring species. Have a look at "The Salamander's Tale" in "The Ancestor's Tale" by Richard Dawkins. It explains how what we call "species" are really little more than arbitrary points along a continuum of constantly changing individuals.