The Saint of the Wilderness Chapter 3

------------------------------------------------

Page 52-54 –Robert’s first encounter with Methodism

===============================

“He gets plumb ornery when he’s had a few,” Clefus explained.

“Next time I get a round I’ll get the tavemkeeper to lace his run with some egg whites. I understand them spirits hide in little balls of egg whites and won’t bust till daylight,” Muley said.

Clefus disagreed. “That won’t do. There won’t be any road between here and Lexington wide enough to keep the wagon in. He sure don’t need no bubbles full of rum abustin’ in his stomach.”

Robert watched Shem sip his rum faster than he should, and instinctively he pushed his own mug away.

“Say, what’s all the people leaving fer?” Clefus asked.

“I ain’t sure,” Muley said, looking toward the door. “Most times they stay till the doors is locked, and the night ain’t hardIy started. I’ll find out for you. Something is goin’ on.” He came back on the run. “They’s a revival happenin’ up over Greenway’s store! Some of the fellers is goin’ and make it hot for the dd sin-socker.”

Clefus shook the arm of Shem and brought his sleepy head from his forearms.

‘’Wrap yourself tight. We’re goin’ to sober you up ill that January weather out there or we’re goin’ to let that-therE evangelist do it fer us. You may be just about right to get saved! How’d you like to wake up in the mornin’ and know you was plumb, teetotally saved!”

Muley laughed as heartily as Clefus, and between them Shem staggered first against one and then the other. The three of them reached the door before Muley relinquished his hold on Shem so that he could pass through the entrance. Robert had not moved.

”You go ahead and tell them I hope they don’t get snowed in before they get back to Baltimore.”

“I ain’t goin’ to do it. Nearly everybody’s left here now. See – there ain’t a dozen people. You know they all saw you here and they’ll be awonderin’ why you didn’t have nerve enough to come and pelt that old sin-socker with corncobs.”

‘He hasn’t done me any harm,” Robert said.

“I been thinkin’ lately – you getting’ too good for us fellers what sweats a little for our livin’?”

“No, that isn’t it.”

Clefus called impatiently from the doorway. He was minus his partner, Shem. “I knowed you wasn’t man enough to be in the volunteers! If we was in battle we couldn’t count on you to reach us the gunpowder. You’d be as scared as a sucklin’ kid. You’re scared of a big-mouthed old preacher!” Muley said.

“I am scared of nothing!”

“Then don’t stand here talkin’ about it. We ain’t goin’ to get seats, and all the corncobs will be gone. Let’s get goin’!”

Muley pulled the bench out of Robert’s path and the way was clear to the door. Robert looked at Muley and the blacksmith grinned wide, until his yellow teeth showed. Robert crossed the distance hurriedly and they were out in the street. Muley called to Clefus, “Let’s get goin’! Make Shem take deep breath of this cold air. If that don’t sober him up it’ll give him a coughin’ fit and shake loose his liver and he can let it all out.”

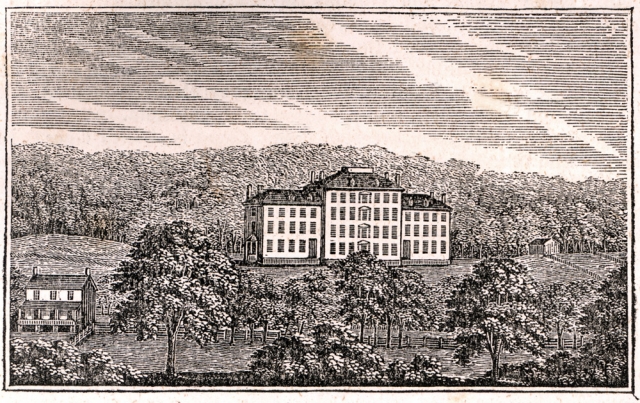

When the four of them reached the top of the stairs over Greenway’s store, the third-floor room still had vacant seats. Robert could tell the serious worshipers from most of the faces he had seen in the tavern. There was little need to draw a line of division, for many of the tavern patrons sat enmasse to the rear of the large room. There could not have been more than twenty-five or thirty people in attendance before the men from the tavern arrived. Now the congregation numbered sixty or seventy. Having come last, Robert could not be certain, but the old man who stood before them, thin but ‘ball, with his bony knees and elbows outlined against his worn clothes, had an inquiring look on his face. It was not hard to see the brightness in the aged man’s eyes when he first began to notice the empty benches starting to fill. Although the revival must have been half finished, the countenance of this old evangelist strongly suggested to Robert his willingness to start the meeting all over again if there were those who would benefit and if their attendance was sincere.

Bony hands caressed each other as the old man tried to smile and welcome the newcomers. The skin of his face was wrinkled and loose, and he stooped slightly, though he tried to stand erect. He walked across the front of the room to pick up something, and the arch of his back became much more apparent. It seemed to start at the base of the spine and continue to the base of the neck – the type of arch a man would develop when he had ridden a horse for many more years than his strength had been sufficient to hold himself erect.

The object the old man fetched was a pitch pipe.

“The Lord has blessed us with many who have come late. Since they have not joined us in fellowship by the singing of a hymn, we will sing together that old hymn you all know, ‘Blessed Be the name of the Lord.’ Sister Louise will pass out the songbooks, but we don’t have many. Please share them with a Christian brother by your side.”

The preacher blew the “C” note on the pitch pipe, and led the singing. Those near the front sang vigorously, but only a few in the back joined in, and then only until they were stared down by their fellow tavern patrons.

By the middle of the second verse the copper kettle sitting to the side of the single Ben Franklin stove began to yield what few corncobs yet remained of the kindling. In the absence of more corncobs, someone reached for wood chips, but an older man nearby squeezed the taker’s wrist until the chips were dropped. “Don’t use chips on him,” the older man whispered. .. We don’t want to kill him – or blind him – we just want to slow him down.”

A corncob was passed to Robert. He held it in his hands for a moment, and passed it on. Not a corncob was in sight when the hymn was concluded; each man concealed his weapon with the same skill with which he concealed his intentions.

Robert knew about when to expect the onslaught. He had heard the men at the tavern talk about how they had carried out this devilment before. They would let the visiting itinerant work himself into a sweat, and when the invitation I penitence was issued the corncobs would begin to fly through the air until the helpless preacher looked like an awkward schoolboy fighting off a swarm of bees.

------------------------------------------------

Page 52-54 –Robert’s first encounter with Methodism

===============================

“He gets plumb ornery when he’s had a few,” Clefus explained.

“Next time I get a round I’ll get the tavemkeeper to lace his run with some egg whites. I understand them spirits hide in little balls of egg whites and won’t bust till daylight,” Muley said.

Clefus disagreed. “That won’t do. There won’t be any road between here and Lexington wide enough to keep the wagon in. He sure don’t need no bubbles full of rum abustin’ in his stomach.”

Robert watched Shem sip his rum faster than he should, and instinctively he pushed his own mug away.

“Say, what’s all the people leaving fer?” Clefus asked.

“I ain’t sure,” Muley said, looking toward the door. “Most times they stay till the doors is locked, and the night ain’t hardIy started. I’ll find out for you. Something is goin’ on.” He came back on the run. “They’s a revival happenin’ up over Greenway’s store! Some of the fellers is goin’ and make it hot for the dd sin-socker.”

Clefus shook the arm of Shem and brought his sleepy head from his forearms.

‘’Wrap yourself tight. We’re goin’ to sober you up ill that January weather out there or we’re goin’ to let that-therE evangelist do it fer us. You may be just about right to get saved! How’d you like to wake up in the mornin’ and know you was plumb, teetotally saved!”

Muley laughed as heartily as Clefus, and between them Shem staggered first against one and then the other. The three of them reached the door before Muley relinquished his hold on Shem so that he could pass through the entrance. Robert had not moved.

”You go ahead and tell them I hope they don’t get snowed in before they get back to Baltimore.”

“I ain’t goin’ to do it. Nearly everybody’s left here now. See – there ain’t a dozen people. You know they all saw you here and they’ll be awonderin’ why you didn’t have nerve enough to come and pelt that old sin-socker with corncobs.”

‘He hasn’t done me any harm,” Robert said.

“I been thinkin’ lately – you getting’ too good for us fellers what sweats a little for our livin’?”

“No, that isn’t it.”

Clefus called impatiently from the doorway. He was minus his partner, Shem. “I knowed you wasn’t man enough to be in the volunteers! If we was in battle we couldn’t count on you to reach us the gunpowder. You’d be as scared as a sucklin’ kid. You’re scared of a big-mouthed old preacher!” Muley said.

“I am scared of nothing!”

“Then don’t stand here talkin’ about it. We ain’t goin’ to get seats, and all the corncobs will be gone. Let’s get goin’!”

Muley pulled the bench out of Robert’s path and the way was clear to the door. Robert looked at Muley and the blacksmith grinned wide, until his yellow teeth showed. Robert crossed the distance hurriedly and they were out in the street. Muley called to Clefus, “Let’s get goin’! Make Shem take deep breath of this cold air. If that don’t sober him up it’ll give him a coughin’ fit and shake loose his liver and he can let it all out.”

When the four of them reached the top of the stairs over Greenway’s store, the third-floor room still had vacant seats. Robert could tell the serious worshipers from most of the faces he had seen in the tavern. There was little need to draw a line of division, for many of the tavern patrons sat enmasse to the rear of the large room. There could not have been more than twenty-five or thirty people in attendance before the men from the tavern arrived. Now the congregation numbered sixty or seventy. Having come last, Robert could not be certain, but the old man who stood before them, thin but ‘ball, with his bony knees and elbows outlined against his worn clothes, had an inquiring look on his face. It was not hard to see the brightness in the aged man’s eyes when he first began to notice the empty benches starting to fill. Although the revival must have been half finished, the countenance of this old evangelist strongly suggested to Robert his willingness to start the meeting all over again if there were those who would benefit and if their attendance was sincere.

Bony hands caressed each other as the old man tried to smile and welcome the newcomers. The skin of his face was wrinkled and loose, and he stooped slightly, though he tried to stand erect. He walked across the front of the room to pick up something, and the arch of his back became much more apparent. It seemed to start at the base of the spine and continue to the base of the neck – the type of arch a man would develop when he had ridden a horse for many more years than his strength had been sufficient to hold himself erect.

The object the old man fetched was a pitch pipe.

“The Lord has blessed us with many who have come late. Since they have not joined us in fellowship by the singing of a hymn, we will sing together that old hymn you all know, ‘Blessed Be the name of the Lord.’ Sister Louise will pass out the songbooks, but we don’t have many. Please share them with a Christian brother by your side.”

The preacher blew the “C” note on the pitch pipe, and led the singing. Those near the front sang vigorously, but only a few in the back joined in, and then only until they were stared down by their fellow tavern patrons.

By the middle of the second verse the copper kettle sitting to the side of the single Ben Franklin stove began to yield what few corncobs yet remained of the kindling. In the absence of more corncobs, someone reached for wood chips, but an older man nearby squeezed the taker’s wrist until the chips were dropped. “Don’t use chips on him,” the older man whispered. .. We don’t want to kill him – or blind him – we just want to slow him down.”

A corncob was passed to Robert. He held it in his hands for a moment, and passed it on. Not a corncob was in sight when the hymn was concluded; each man concealed his weapon with the same skill with which he concealed his intentions.

Robert knew about when to expect the onslaught. He had heard the men at the tavern talk about how they had carried out this devilment before. They would let the visiting itinerant work himself into a sweat, and when the invitation I penitence was issued the corncobs would begin to fly through the air until the helpless preacher looked like an awkward schoolboy fighting off a swarm of bees.

Upvote

0