Already on it. It's in the main forum:

A couple of days ago, my blog neighbor Deacon Greg Kandra shared a news item about a

. The story is noteworthy because the Catholic hospitals’ legal defense team argued that while the patient (who died seven years ago), Lori Stodghill, was indisputably a person, they noted that under Colorado law, her unborn twins, 28 weeks of gestation at the time of death, are not considered persons.

As you might imagine, given the Catholic Church’s belief that human life, and thus personhood, begins at conception, this line of defense has been seen as a controversial one. Another of my blog neighbors, Mark Shea, stated it like this:

.

Yesterday, chancellor J.D. Flynn of the Archdiocese of Denver published the following

.

The Catholic bishops of Colorado learned recently of the deaths of Lori Stodghill and her two unborn children, which took place at St. Thomas More Hospital in Cañon City, Colo. in 2006. We wish to extend our solidarity and sympathy to Lori’s husband Jeremy, and her daughter, Elizabeth. Please be assured of our ongoing prayers.

From the moment of conception, human beings are endowed with dignity and with fundamental rights, the most foundational of which is life.

Catholics and Catholic institutions have the duty to protect and foster human life, and to witness to the dignity of the human person—particularly to the dignity of the unborn. No Catholic institution may legitimately work to undermine fundamental human dignity.

Catholic Health Initiatives is a Catholic institution which provides health care services in 14 states, providing care to thousands of people annually. Catholic Health Initiatives has been accused by some of undermining the Catholic position on human life in the course of litigation. Today, representatives of Catholic Health Initiatives assured us of their intention to observe the moral and ethical obligations of the Catholic Church.

The Catholic bishops of Colorado are not able to comment on ongoing legal disputes. However, we will undertake a full review of this litigation, and of the policies and practices of Catholic Health Initiatives to ensure fidelity and faithful witness to the teachings of the Catholic Church.

Most Rev. Samuel J. Aquila, S.T.L., Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Denver

Most Rev. Michael Sheridan, S.Th.D, Bishop of the Diocese of Colorado Springs

Most Rev. Fernando Isern, Bishop of the Diocese of Pueblo

Here is why this lawsuit matters. As it turns out, in part because of the hospitals’ counsel pointing out the fact that under Colorado law a fetus is not considered a person, the Colorado Supreme Court may have to tackle the issue of personhood head-on.

Although the Church believes and teaches that life, and by extension personhood, begins at conception, the legal framework under which this lawsuit must be decided is that of the state where the case is being tried. The legal system of Colorado, and precedents established in case law there, are what matters in the adjudication of this case. Thus the definition of personhood, and whether a fetus is recognized as a person or not, matters in this case not so much because the Church, and a hospital operating as one of her agents, believes a fetus is a person, but because Colorado doesn’t recognize this as the law reads currently. Thus the nuance of the seemingly hypocritical argument by lawyers that the hospital can’t be sued for the wrongful death of patients that the state doesn’t recognize as persons, gets lost in the brouhahah.

, gives the best in-depth report on this case that I have seen. In an article published yesterday entitled,

the twists and turns that have occurred over the years since Lori, and her twins, passed on to eternity, are painstakingly detailed by Asmar below. Though she was not able to get comments from the attorneys of the doctors (Dr. Pelner, and Dr. Staples), or the hospital that are involved in the case (or from the Archdiocese), she spoke with scholars from both within the Catholic tradition, and outside of it, to put together the following recap of the case to date.

The doctrine of the Catholic Church is clear: Fetuses are life, and life must be protected.

“We treat life as if it begins at conception and continues until natural death,” says Sister Peg Maloney, a member of the religious-studies faculty at

Regis University, a Jesuit college in Denver. Because Catholics believe unborn babies are people, “it’s a belief that certainly there was more than one patient involved in this case,” Maloney adds.

The Diocese of Pueblo, which covers Cañon City, likewise refused to answer questions about Catholic Health Initiatives’ argument. Instead, a spokeswoman referred us to the Colorado Catholic Conference, which describes itself as “a united voice of the three Catholic dioceses [that] speaks on public policy issues.” But a spokeswoman for that organization did not return phone calls or e-mails. The Catholic Health Association of the United States also declined to weigh in: “We will pass on an interview,” a spokesman wrote in an e-mail.

But many answers can be found in a guide to moral issues in Catholic health care that is published by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Called “

Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services,” the most recent edition was released in 2009 and includes an entire section on the beginning of life.

“The Church’s defense of life encompasses the unborn and the care of women and their children during and after pregnancy,” the guide says.

The guide goes on to list dos and don’ts for health-care providers. Do encourage natural family planning. Don’t allow the use of contraceptives. Do counsel couples toward adoption. Don’t offer “reproductive technologies that substitute for the marriage act.” Never perform an abortion. Never perform a vasectomy. Always provide prenatal care to expectant mothers. Do induce labor if the mother is suffering from a medical condition and the baby is viable.

Given those beliefs, Catholic Health Initiatives’ legal argument is hypocritical, says Miguel De La Torre, a professor of social ethics at Denver’s

Iliff School of Theology. “What they should be arguing is, ‘Oh, no, all life, from the moment of conception, is life and therefore must be protected,’” De La Torre says.

“When you establish yourself in this culture as a moral voice, even when it works against you, you have to maintain that moral voice.”

But Sister Maloney says that the intersection of religious beliefs and law isn’t that simple.

The hospital’s attorneys aren’t “trying to argue whether unborn children should be recognized as persons,” she says. “They’re just arguing that they are not in Colorado law.”

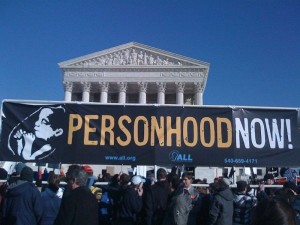

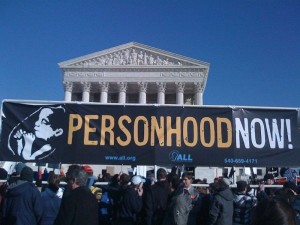

She points out that Colorado voters have twice rejected, in 2008 and 2010, so-called personhood amendments that would have defined the word “person” as indicating any human being from the moment of conception. Catholic leaders didn’t support the pro-life measures because they didn’t think a constitutional amendment was the solution.

“We remain committed to defending all human life from conception to natural death,” the archbishop of Denver and the bishops of Pueblo and Colorado Springs wrote in a joint statement in 2008. But, they added, “even if this year’s personhood amendment is passed in Colorado, lower federal courts interpreting this amendment will be required to apply the permissive 1973 Roe v. Wade abortion decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.”

The bishops have, however, supported other measures to protect the unborn, including efforts to increase penalties for attacks on pregnant women and a bill to require pregnant women seeking abortions to be notified that they can first have an ultrasound. For the past five years, the Colorado Catholic Conference has supported bills to make killing a fetus illegal.

Still, University of Denver law professor Tom Russell believes that the hospital’s argument is legally sound. “All they’re doing is saying here’s what the legislature said,” says Russell, a torts specialist. “It might make some people within the church uncomfortable, but legally, it’s not in any way problematic.”

But David Weddle, a religion professor at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, says that while the hospital is free to make any legal argument it wants, the question is “whether it’s morally justifiable to defend yourself on a principle you know to be false.

“It would send a very strong message if this hospital were to say, ‘We are not legally liable here, but we accept responsibility because we believe that these fetuses were persons,’” Weddle continues. “That’s the only consistent argument the church can make.”

*********

(Drs.) Pelner and Staples soon joined Catholic Health Initiatives in its argument, and also noted that Colorado’s wrongful-death law simply says that survivors can seek compensation for the wrongful death of “a person.” It makes no mention of fetuses.

To be considered a person, the lawyers argued, a baby has to be born alive. As proof, they cited a 2008 case in which doctors performed a C-section on a woman who was five months pregnant when she was in a car accident that caused her placenta to detach from the uterine wall. A Colorado appeals court ruled that she could sue the driver who caused the crash because the premature baby lived briefly — even if it was only for an hour and six minutes.

Jeremy’s lawyers think the hospital’s argument twists the purpose of the wrongful-death law. The point of the law is to make sure that someone who injures another person so badly that he dies doesn’t get away with it because the victim is no longer alive to take him to court.

“What we’re saying is if you have a viable fetus — and there’s no question in this case that these babies were viable — and a doctor negligently causes their death, that the surviving parents ought to be able to bring a lawsuit,” says lawyer Beth Krulewitch, who along with attorneyDan Gerashtook over Jeremy’s case from Woodruff. To deny the parents that right would open up the

The Colorado Supreme Court

very loophole that the wrongful-death law seeks to close, Krulewitch argues.

“The person who was negligent would basically get away with it,” she says.

Fremont County District Court Judge David Thorson disagreed. In December 2010, he sided with Catholic Health Initiatives and the doctors, and dismissed Jeremy’s lawsuit.

But Thorson noted that no appeals court in Colorado had taken up the issue of whether fetuses are people under the law, leaving it an open question. He also noted that the word “person” isn’t defined in the statute. If lawmakers meant it to cover unborn babies, he ruled, they would have said so.

Thorson threw out the lawsuit related to Lori, as well. Based on expert testimony, he decided that the blockage of her arteries was so severe that she probably would have died whether or not the doctors had performed a C-section to save the twins.

Jeremy was crestfallen, and even though he was forced to declare bankruptcy after the doctors and the hospital came after him for $118,969 in legal fees, he decided to appeal.

Nine months later, in August 2011, Jeremy’s lawyers filed a brief asking a panel of three appellate judges to reverse the district court ruling. To back their case, they cited several cases from inside and outside Colorado. One of the most important was a 1986 decision by former Colorado Supreme Court justice and then-U.S. District Court judge James Carrigan. Faced with a situation in which a nine-months-pregnant woman was killed by a drunk driver, Carrigan found that the woman’s husband could sue the bar that served the driver for the wrongful death of both his wife and unborn son.

The purpose of the wrongful-death law, Carrigan wrote, is to “preserve and protect human life.” That includes, he added, “a full-term, viable unborn child’s right to be born alive.”

The case was heard in federal court because of what’s known as diversity jurisdiction, which means that the people involved are citizens of different states or countries. Since the accident happened in Colorado, Carrigan had to interpret Colorado law in making his decision. But federal court decisions aren’t binding on future state cases.

Even so, Jeremy’s lawyers argued that Carrigan’s ruling “provides a thoughtful and persuasive framework.” They also pointed out that courts in at least thirty other states have found that a viable fetus is a “person” under their wrongful-death laws, many of which resemble Colorado’s law. The Colorado Trial Lawyers Association joined in that argument by filing its own legal brief, writing that “common sense, common decency and the majority of courts” support the conclusion that the law should cover viable unborn babies.

*********

The hospital and doctors continued to do battle. But there was a dawning realization in their legal briefs that the issue of fetuses-as-people could be a public-relations disaster.

“Whenever the legal system addresses the rights of the unborn, political winds swirl and passionate debate mounts,” the hospital’s lawyers wrote.

Soon thereafter, the lawyers for Pelner and Staples appear to have switched their tactics, encouraging the court to decide the case based on another reason altogether, which the court is allowed to do: that the OB-GYN expert hired by Jeremy’s lawyers “did not know whether a C-section would have saved the fetuses.” If it wouldn’t have helped anyway, should Jeremy be allowed to sue the doctors and hospital for not performing it?

That’s the question the three appellate judges were interested in when lawyers met to argue the case in April 2012. To prove their point, the doctors’ lawyers relied on a snippet of testimony taken from the OB-GYN expert’s deposition.

The expert was questioned about perimortem C-section, or a C-section performed at or near the time of a mother’s death. When asked if “overall, to a probability,” most babies born by perimortem C-section die, he answered in the affirmative.

But Krulewitch argued that the doctors’ lawyers took the expert’s answer out of context. He only said yes after he was told to disregard how quickly the procedure is done. If a perimortem C-section is performed within five minutes of a mother going into cardiac arrest, the expert testified, the chances of a baby surviving are good.

Perinatologist Vern Katz, who wrote the first paper on perimortem C-sections in 1986, says the standard about when to do one is clear: Start the procedure within four minutes so that the baby can be delivered within five minutes, before brain damage begins.

“You don’t listen to [fetal] heart tones, because you can’t really tell,” says Katz, a clinical professor at Oregon Health and Science University. That’s because when an unborn baby is in distress, its heartbeat can slow dramatically, making it hard to detect, he explains. Plus, he says, the emergency room is often hectic. “There’s yelling and screaming and moving the mom around. It’s very chaotic, and you can’t verify whether heart tones are there.

“We say, ‘Just go for the baby, period,’” he adds.

A pulmonary embolism, which is what Lori suffered, is “a great reason to do a perimortem C-section,” Katz explains. Even if the mother can’t be saved, you’re “doing it to save the baby.” At 28 weeks along, he says, “the babies would have been resuscitatable.”

In many cases, doing a C-section within five minutes isn’t possible. But it was in Lori’s case. “Lori was rolled into the emergency room living and breathing,” Gerash says. “The unborn fetuses are in the place where they have the best chance.”

But the appellate judges agreed with the doctors, ruling last August that Jeremy “failed to produce any evidence” that the doctors’ negligence caused the twins to die.

As for the question of whether fetuses are people under Colorado’s wrongful-death law, they left it unanswered, and DU law professor Russell understands why. “No judge in the state wants to be the judge who decides the issue,” he says. “Almost no judge wants to write an opinion that says, ‘Here’s what the wrongful-death statute means.’ One way or another, they’re going to get a lot of heat for it.”

Jeremy and his lawyers, however, believe the issue needs to be decided. So in September, despite their repeated losses and mounting legal costs, they appealed to the Colorado Supreme Court.

Jeremy’s lawyers are asking the high court to answer three questions: Was the appeals court wrong in dodging the issue of whether Jeremy’s unborn sons were “people” under the law? Was the appeals court wrong to instead dismiss Jeremy’s lawsuit based on that snippet of testimony? And was the court wrong in deciding that the testimony cast doubt on whether the babies would have survived, when it “was subject to more than one reasonable interpretation”?

There is no deadline by which the Supreme Court must decide whether to take the case. If it does, the justices could remand the case back to the appeals court with instructions to decide whether fetuses are people under the wrongful-death law. Or they could answer the question themselves. If they decide fetuses aren’t people, the case is over. If they decide they are, Jeremy will be entitled to bring the issue to trial. “The big reason I want to get back into court,” Jeremy says, “is to be able to ask why they didn’t try to save the boys.”

.

One way, or another, the legal definition of personhood will have to be decided upon. After all, its meaning was bandied about during the Roe vs. Wade arguments,

Due to cases like the one involving St. Thomas More Hospital as outlined above, forty years of ducking the issue may be rapidly coming to a close.

.